Measles is a highly contagious viral infection caused by the measles virus (Measles morbillivirus), which belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family. The disease presents with characteristic symptoms including a distinctive maculopapular rash, high fever reaching 40°C (104°F), and respiratory manifestations such as cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. While the measles virus primarily infects the respiratory tract, it demonstrates systemic tropism, potentially affecting multiple organ systems including the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and immune system.

Prior to vaccine introduction in 1963, measles was endemic worldwide, causing an estimated 2.6 million deaths annually. The implementation of comprehensive vaccination programs using the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine has reduced global measles incidence by approximately 73% between 2000 and 2018. Despite this progress, measles remains a leading cause of vaccine-preventable deaths among children globally, with an estimated 207,500 deaths in 2019.

The measles virus is a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA virus measuring 100-300 nanometers in diameter. Transmission occurs primarily through airborne respiratory droplets and aerosols generated during coughing, sneezing, or talking. The virus demonstrates exceptional contagiousness, with a basic reproduction number (R₀) of 12-18, meaning one infected individual can transmit the disease to 12-18 susceptible persons.

The virus can remain viable in air for up to two hours and on surfaces for several hours under appropriate conditions. Measles complications occur in approximately 30% of cases and include pneumonia (the most common cause of measles-related death in children), encephalitis (occurring in 1 per 1,000 cases), and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (a rare but fatal delayed complication). Case fatality rates vary from less than 0.1% in developed countries to over 10% in populations with high rates of malnutrition and limited healthcare access.

Contemporary measles outbreaks continue to emerge in communities with vaccination coverage below the 95% threshold required for herd immunity, emphasizing the critical importance of maintaining high immunization rates for disease control and elimination efforts.

Key Takeaways

- Measles is a highly contagious viral disease characterized by fever, cough, and a distinctive rash.

- It spreads through respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes of infected individuals.

- Symptoms include high fever, cough, runny nose, and rash; complications can be severe, especially in young children.

- Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent measles and control outbreaks.

- Protecting yourself and others involves staying up-to-date with vaccines and practicing good hygiene.

How Measles Spreads

Measles spreads primarily through respiratory droplets that are expelled when an infected person coughs or sneezes. These droplets can travel through the air and be inhaled by individuals nearby, leading to new infections. The virus is so contagious that approximately 90% of non-immune individuals who are exposed to it will contract the disease.

This high level of transmissibility is one of the reasons why measles outbreaks can occur rapidly in populations with low vaccination rates. In addition to airborne transmission, measles can also spread through direct contact with contaminated surfaces or objects. The virus can survive on surfaces such as tables, doorknobs, and clothing for several hours.

If a person touches a contaminated surface and then touches their mouth, nose, or eyes, they can become infected.

Furthermore, individuals infected with measles are contagious from about four days before the onset of the rash to four days after it appears, making it challenging to control outbreaks once they begin.

Symptoms and Complications of Measles

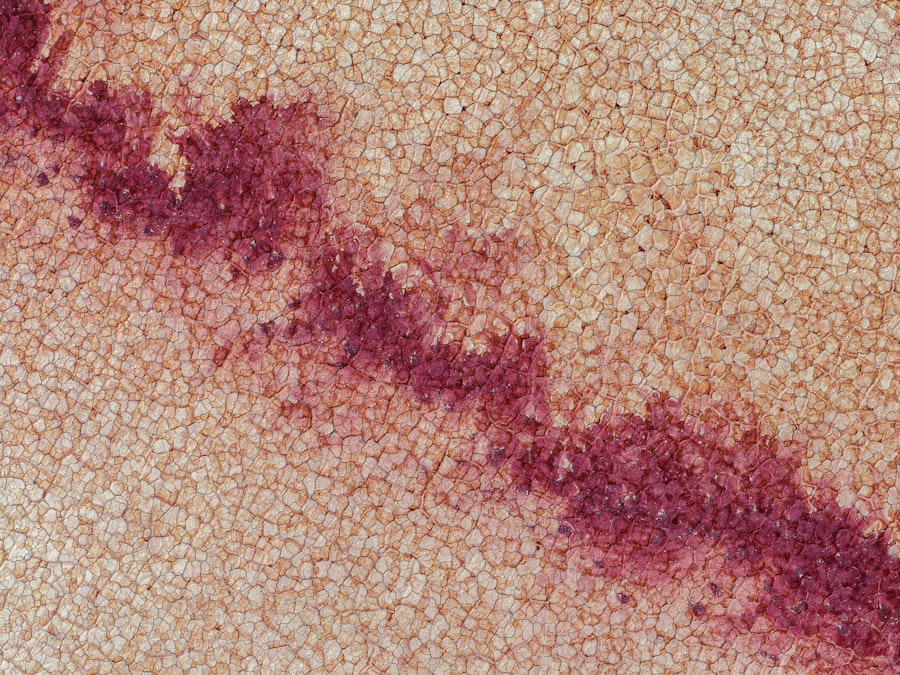

The symptoms of measles typically appear 10 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. Initial symptoms often resemble those of a common cold and include high fever, cough, runny nose, and conjunctivitis (inflammation of the eyes). As the disease progresses, a characteristic red rash develops, usually starting on the face and spreading downward to the rest of the body.

The rash typically appears three to five days after the initial symptoms and can last for several days. Complications from measles can be severe and include pneumonia, which is one of the most common causes of death associated with the disease. Other serious complications include encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain that can lead to permanent neurological damage or death.

Additionally, individuals with weakened immune systems or underlying health conditions are at a higher risk for severe complications. The risk of complications increases with age; adults are more likely to experience severe illness than children. In some cases, individuals may also develop subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a rare but fatal progressive neurological disorder that can occur years after measles infection.

Who is at Risk?

While anyone who is not vaccinated against measles is at risk for infection, certain groups are particularly vulnerable. Infants who are too young to receive the measles vaccine (typically administered at 12 months of age) are at high risk if they are exposed to the virus. Additionally, individuals with compromised immune systems—such as those undergoing chemotherapy or living with HIV—are more susceptible to severe complications from measles.

This includes people who have chosen not to vaccinate due to personal beliefs or misinformation about vaccine safety. In some communities, particularly those with strong anti-vaccine sentiments, outbreaks can occur when a single case is introduced.

Furthermore, international travelers who visit areas where measles is still prevalent may unknowingly bring the virus back to their home countries, posing a risk to unvaccinated populations.

Measles Vaccination and Prevention

| Metric | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Incubation Period | 10-14 days | Time from exposure to symptom onset |

| Contagious Period | 4 days before to 4 days after rash onset | Highly contagious during this period |

| Basic Reproduction Number (R0) | 12-18 | Indicates high transmissibility |

| Vaccine Effectiveness | 93% (1 dose), 97% (2 doses) | MMR vaccine effectiveness |

| Global Annual Cases (pre-vaccine era) | ~30 million | Estimated before widespread vaccination |

| Global Annual Deaths (pre-vaccine era) | ~2.6 million | Estimated before widespread vaccination |

| Current Global Mortality Rate | ~0.1-0.2% | Varies by region and healthcare access |

| Common Complications | Pneumonia, Encephalitis, Diarrhea | Can lead to severe illness or death |

| Recommended Vaccination Age | 12-15 months (1st dose), 4-6 years (2nd dose) | Varies by country guidelines |

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent measles and its associated complications. The measles vaccine is typically administered as part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, which provides immunity against all three diseases. The first dose of the MMR vaccine is usually given between 12 and 15 months of age, with a second dose recommended between ages 4 and 6 years.

This two-dose schedule has been shown to provide long-lasting immunity. Public health campaigns emphasize the importance of achieving herd immunity—when a significant portion of a population is vaccinated—thereby protecting those who cannot be vaccinated due to medical reasons or age. Herd immunity helps prevent outbreaks by reducing the overall amount of virus circulating in the community.

In areas where vaccination rates fall below 95%, outbreaks become more likely. Therefore, it is crucial for communities to maintain high vaccination coverage to protect vulnerable populations and prevent the resurgence of measles.

Current Measles Outbreaks

As of late 2023, several regions around the world continue to experience measles outbreaks due to declining vaccination rates and increased travel. Countries in Europe have reported significant increases in measles cases over recent years, often linked to vaccine hesitancy and misinformation about vaccine safety. For instance, countries like Romania and Ukraine have faced severe outbreaks that have resulted in numerous hospitalizations and fatalities.

In the United States, while measles was declared eliminated in 2000 due to effective vaccination programs, sporadic outbreaks have occurred in recent years. These outbreaks are often traced back to unvaccinated individuals who traveled internationally or were part of communities with low vaccination rates. Public health officials have responded by implementing targeted vaccination campaigns and educational initiatives aimed at increasing awareness about the importance of immunization against measles.

Understanding the Impact of Measles on Public Health

The impact of measles on public health extends beyond individual cases; it poses significant challenges for healthcare systems and communities as a whole. Measles outbreaks can lead to increased healthcare costs due to hospitalizations and treatment for complications. Moreover, they can strain healthcare resources, particularly in areas already facing challenges such as limited access to medical care or high rates of other infectious diseases.

Additionally, measles has broader implications for public health initiatives aimed at controlling infectious diseases. The resurgence of measles highlights vulnerabilities in vaccination programs and underscores the need for ongoing public education about vaccine safety and efficacy. It also serves as a reminder that complacency regarding childhood vaccinations can lead to preventable diseases re-emerging in populations that had previously achieved high levels of immunity.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself and Others

Protecting yourself and others from measles begins with ensuring that you and your family are up-to-date on vaccinations. If you are unsure about your vaccination status or that of your children, consult with a healthcare provider who can provide guidance based on your medical history and local vaccination recommendations. For adults who were not vaccinated as children or who may have missed doses, it is never too late to receive the MMR vaccine.

In addition to vaccination, practicing good hygiene can help reduce the risk of spreading infectious diseases like measles. Regular handwashing with soap and water, especially after being in public places or after coughing or sneezing, is essential in preventing transmission. If you are feeling unwell or exhibit symptoms consistent with measles, it is important to stay home and avoid contact with others until you have consulted a healthcare professional.

Community engagement plays a vital role in preventing outbreaks as well. Advocating for vaccination within your community and addressing concerns about vaccine safety through education can help increase overall immunization rates. By fostering an environment where accurate information about vaccines is shared and discussed openly, communities can work together to protect their most vulnerable members from preventable diseases like measles.

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease that can lead to serious health complications, making vaccination crucial for prevention. For those interested in understanding more about health and wellness, you might find the article on essential lower back stretches helpful, as maintaining overall health can support a robust immune system. You can read it here: 10 Essential Lower Back Stretches for Relief.

FAQs

What is measles?

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease caused by the measles virus. It primarily affects children but can occur at any age. The disease is characterized by symptoms such as high fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, and a distinctive red rash.

How is measles transmitted?

Measles spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It can also be transmitted by direct contact with nasal or throat secretions of infected individuals. The virus can remain active and contagious in the air or on surfaces for up to two hours.

What are the symptoms of measles?

Symptoms typically appear 7 to 14 days after exposure and include high fever, cough, runny nose, red and watery eyes (conjunctivitis), and Koplik spots (small white spots) inside the mouth. A red, blotchy rash usually appears a few days after the initial symptoms, starting on the face and spreading downward.

How serious is measles?

Measles can be serious and sometimes fatal, especially in young children and individuals with weakened immune systems. Complications may include ear infections, diarrhea, pneumonia, encephalitis (brain swelling), and death.

Is there a vaccine for measles?

Yes, the measles vaccine is safe and effective. It is usually given as part of the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine. Two doses are recommended for full protection, typically administered during childhood.

Can measles be treated?

There is no specific antiviral treatment for measles. Care focuses on relieving symptoms, such as fever and cough, and preventing complications. Vitamin A supplements are often recommended to reduce the severity of the disease.

How can measles be prevented?

The best prevention is vaccination. Maintaining high vaccination coverage in the community helps prevent outbreaks. Other preventive measures include isolating infected individuals and practicing good hygiene, such as frequent handwashing.

Who is at risk of contracting measles?

Anyone who is not vaccinated or has not had measles before is at risk. Infants too young to be vaccinated, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals are particularly vulnerable to severe disease.

What should I do if I suspect someone has measles?

If measles is suspected, it is important to seek medical advice promptly. The infected person should avoid contact with others to prevent spreading the virus. Healthcare providers may report cases to public health authorities to help control outbreaks.

Can adults get measles?

Yes, adults who have not been vaccinated or previously infected can contract measles. Adult cases can sometimes be more severe than in children. Vaccination is recommended for adults without evidence of immunity.